Pacific Island pride and heritage are bringing vibrant colors to the cornfields of southwest Iowa. Micronesians, or Islanders (a self-attributed term), who originate from the islands in or surrounding the Federated States of Micronesia, are expanding the Atlantic community. In honor of Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, this story hopes to shine a light on the cultural features of our community’s Islander population.

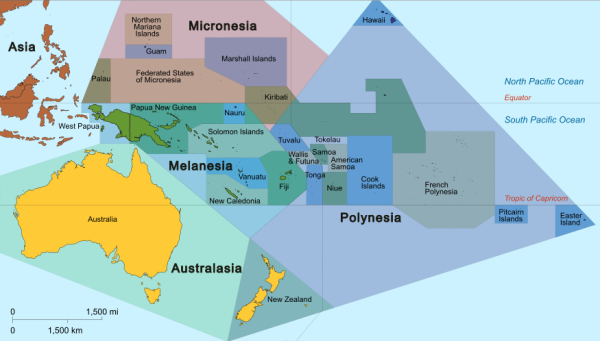

Geography

Micronesia as a region is a term that refers to over 2,100 islands near Oceania in the western Pacific Ocean. The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) is a country comprised of over 600 islands and four main island states: Pohnpei, Kosrae, Yap, and Chuuk, the latter of which is the birthplace of many Islanders in Cass County. These island states may contain several island groups within them as well. There’s also Guam, a United States territory 632 miles northwest of Chuuk, as a shared birthplace for some Atlantic residents.

Micronesian natives are just one of several groups under the Pacific Islander umbrella. It’s important to note that Micronesia is a separate entity from Polynesia, a set of islands occupying a different region in the Pacific Ocean, and Hawaii, a United States state in a different part of the Pacific Ocean.

Language and Names

Even if two islands start with the same base language, the distance between these islands can cause minor to significant differences in language, and this relationship accounts for nearly every island in Micronesia. The primary language spoken in the Chuuk state is Chuukese, but senior Markes Mark said that his family uses slightly different words than standard Chuukese because of his parents’ nativity to the Chuuk island of Losap. The distance between islands also accounts for the large difference between Chuukese and Chamorro, a language spoken in Guam. Contemporary Chamorro shares several words with Spanish and is closest to some Filipino and eastern Indonesian languages.

Some students may learn English in school on the islands. Because of the prominence of English within Cass County, languages like Chuukese or Chamorro are mainly used within the Islander community or at home to communicate with elder members who may not be fluent in English. This results in bilingualism, the understanding of two or more languages. Freshman Shining Meither could understand three languages – Chuukese, Chamorro, and English – by the time she moved to the United States in 2020, and is currently teaching herself a fourth language in order to connect further with her heritage.

Every Islander within Atlantic has at least one given name and one surname, but may also have a publicly-used nickname. This is referred to within the student Islander community as “home” names and “school” or “public” names. “Home” names are often passed down by one family member to another, sometimes in combination with other family names. Freshman AK Hartman’s unique name was derived from members of his family, and at home, he is called KK or Kaykay. Meither’s home name is derived from her grandmother, and while junior Engiengkiboss Made uses his first name in all situations, his name is a combination of three different names: his grandfather’s nickname Engi, his full name Engkichy, and his great-grandfather’s name Bossy.

Important Values

If you ask someone from Micronesia or the surrounding islands what their most important values are, many will say respect and family. Respecting your relatives, especially the older generation, is essential, since many offer wisdom and direction to the younger generation. Family is also an integral part of Islander culture: this is especially true within a tight-knit community such as Atlantic’s.

Keeping tradition alive is an important act. Without tradition, many important cultural aspects such as values would be lost. Adapting tradition and sharing it with others is one way that members of the community honor their roots and keep their culture alive.

Cultural Expression

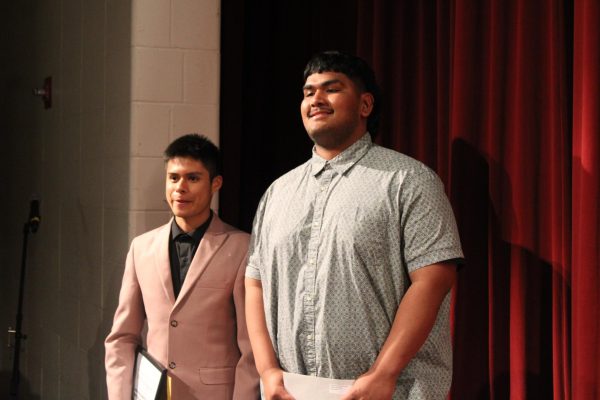

The freedom to express one’s unique background or experiences is an idea that many Islanders share, which is also a core American value. One part of this is “putting Micronesia on the map,” which means giving recognition to the underrepresented people of Micronesia. Reed “Sunny” Flaisek, a senior, plans to play football while attending Ellsworth Community College in Iowa Falls, Iowa. One of his motivators for career success is representing Micronesians like himself. Flaisek said, “I really haven’t seen [Micronesians] make it to the top…. I’m trying to make a difference and make it to the top.”

Before moving to Atlantic, junior Saleimor Rax lived in Portland, Oregon. There, he partook in his school’s AAPI club, and believes that Atlantic could benefit from hosting a similar club. Rax was also one of several Micronesian students who ran into the 2024 Homecoming pep rally, all bearing the flags of the United States, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Chuuk. Made, who bore a flag that day, said, “I feel proud. Proud to be an islander and representing [us] in front of all of [those] people. Running out there with the flag is just amazing.”

The flags of Micronesia, Chuuk, and Guam all hold special meaning to the school’s Islander community, and displaying this flag is special in its own way. It doesn’t stop at pep rallies: the stars and blue background of the FSM flag can be seen on students’ hats, hoodies, t-shirts, and even senior Kreboy Esa’s football banner. Freshman Boboy Wallipy said that he has a collection of at least seven personal items at home that all display the flag of Chuuk.

Special Events

If traditional American parties are at a level 10, Islanders like to crank that dial higher. Junior Kesarina Esa said that for special events, “we go all out, it’s big.” Weddings and graduation parties become the hosts of singing, traditional dancing, and hand-made decorations. Dollar bills and candy are strung onto thread to create unique leis, which are often gifted to people whom are being celebrated at a given event. Leis can also incorporate flowers and ribbons. Money is seen not only as a gift, but as a decoration that has a purpose beyond being displayed, and the same goes for candy leis. Islanders also like to put emphasis on children’s first birthdays. These special occasions are the centers of joy, pride, tradition, and honor all at the same time.

Hula

Hula is a traditional dance performed mainly by women, passed down from generation to generation. Senior Nerensia Narios has been dancing hula since childhood; her first performance was in kindergarten, in a “little gathering in Washington [Elementary School]. And of course I was nervous. I was a bit stiff. From then on I started liking performing for people.” To hula dance, one can dance alone or with a group, and these dances typically occur at special events. Narios’ sisters helped start the tradition of hula dancing during the homecoming pep rallies. “It’s like relieving because we’re showing our culture as well.” A hula dance sets traditional or contemporary dances to different music. Narios said that for her family, they focus on the beat of the music when picking a dance track, whereas other hula dancers may choose music with a story.

Religion and Beliefs

The most prominent religion in Atlantic’s Islander population is Christianity. Engiengkiboss Made moved to the United States from Guam to pursue a career in ministry. Now he is an ordained pastor at one of Atlantic’s church congregations that cater to the town’s Islander population. He preaches in Chuukese, leads worship, and teaches faith to the church’s youth – all as an 18-year-old who attends school. “It’s my life,” Made said about faith. “I’m here in the US because of ministry.”

There are also non-religious beliefs shared between Micronesian and Islander households. An example of this is the sacred nature of women’s hair. Micronesian women are encouraged to grow their hair long, and families vary in their views of trimming or dying hair. It’s tradition for women to have their hair cut only by other women who they are close to. In the occasion that a high-ranking member of the family, church, or FSM passes away, cutting their hair short is a sign of respect. Another practice is to deep-clean the house around New Year’s to start the year fresh and get rid of bad spirits.

The most common sentiment between Islander students at AHS is that they’d like more positive Islander representation to be shown. Kesarina Esa said one thing the general Atlantic population gets wrong about her community is “that we cause trouble.” One thing she would like everyone to know is “that we’re very respectful. Because [people] think wrong about us.” Mark said that he wants to see more Micronesian pride within the school. He said, “if there was more, it would definitely help people see our [Micronesian] people in the school…. The students here, I really think they wanna learn more about our culture and everything.” Every Micronesian and Islander is different from one another, but one thing is clear: the vibrant nature of their culture is adding to our Trojan CommUNITY in their own terms.

Kellie Nath • May 19, 2025 at 11:37 pm

Thank you for this wonderfully informative article.

Oscar Jeej • May 16, 2025 at 1:34 pm

Sal is NOT a junior but fire story well done

Jo Molina • Jul 11, 2025 at 10:52 am

Fixing this soon, thank you.